- Home

- Alicia Scott

Marrying Mike...Again Page 4

Marrying Mike...Again Read online

Page 4

“I’m—I’m okay. And you?”

“Fine.” He shrugged, smiled wryly. “You know me. Always fine.”

She smiled. Yes, fine was definitely Mike’s favorite word. “And your family?”

“Good. Chris is getting married. The last Rawlins to go. He found himself a naval pilot if you can believe that. The woman can not only out throw him on the football field, but she can also fly rings around him. So far we’re threatening to accept her into the family and kick him out.”

“I can imagine.” Mike’s family had threatened to kick her out, too. Definitely no love lost there. Belatedly Mike seemed to realize he’d touched a nerve, and he moved hastily to a fresh subject.

“And your family?”

“Same as usual. Mom has her bridge club and new interior decorator. She’s happy. The firm’s still growing, so dad’s happy.” They’re relieved we’re divorced, but no need to say that. Mike knew her parents loved him about as much as his parents had loved her.

“What’d they think of you getting into law enforcement?”

“That I’m nuts.”

“Same old, huh?”

“Yeah, same old. I imagine your parents had a few choice words about you getting to work for me.”

“They’re still rolling on the ground laughing.”

“It is ironic, isn’t it?”

“Hey, you know me. All water under the bayou.”

“Yeah,” she said softly, and had to look away. “Yeah.”

Mike finally rose to his feet. He turned the chair around and placed it back in front of the desk. He kept studying her with dark, unreadable eyes. “So are you seeing anyone, Sandy?”

She hesitated, caught off guard by this line of questioning. “No. You?”

“Nah, nothing serious.”

“With you, I didn’t think they ever were serious.”

“It had been with you, ma chère. It had been with you.”

He strode for the door. It was just as well. Sandra’s heart was beating too fast in her chest now and she couldn’t think of a thing to say.

At the last minute, however, his hand on the knob, Mike turned around. That look was back in his eyes. Dark, somber, searching.

“It wasn’t so bad,” he said softly. “You and me. Our marriage wasn’t so—”

“Mike, look me in the eye and tell me you were happy. Look me in the eye and tell me our marriage was the best year of your life.”

He couldn’t do it. And they both knew it.

After a moment, he turned around. He ripped open the door with more force than necessary. He slammed it shut behind him. He stormed down the hall.

And that made Sandra think back to other days, to the last day. The day she announced with a pounding heart and sweating hands that their marriage was over. And in stead of saying no, instead of finally fighting for her or at least taking her in his arms and telling her it would be all right, Mike had simply said, “Fine.”

Fine. Mike Rawlins’s signature word. Fine.

That had been the day Sandra had finally stopped loving her husband and had learned to hate him instead.

“What the hell kind of assignment is this?”

“The easy kind.”

“Let me see if I got this straight. We identify who this Vee kid is. We track him down. We talk to his family and friends. And then we just walk away? We turn our backs on some cop-threatening punk and write up a report on the subject instead? This,” Koontz said seriously, “is what happens when you put a woman in charge.”

“Welcome to the nineties,” Mike told him, and resumed tapping on the keyboard. “She does have a good point about him writing the letter, though.”

“Conjecture. We’re risking our necks for conjecture.”

“When has it ever been any other way?”

Koontz scowled. He always got annoyed when Mike was right. He hunkered down by the computer, where Mike was perusing the gang database for Vee’s name. Koontz was actually the more computer literate of the two, but he hated to work the keyboard when other cops were around. Looked too clerical.

“You were in her office for a long time,” Koontz said.

“It’s called a debriefing, man. You should try showing up for one sometime.”

Koontz wasn’t fazed. “That was some suit she was wearing,” he observed next. “Showed off just enough curves and class to intimidate us poor working stiffs. Except for you, of course. You always did go for the uptown type.”

Mike kept his eyes glued to the computer screen. Koontz shook his head in disgust.

“Ah, man, I’m right, aren’t I? You’re going soft on her again. One look and you’re like a junkie desperate for a fix. Didn’t you listen to what I told you? When you go into her office, stick to business. Say nothing more, nothing less. In and out quick.”

“The meeting was quick.”

“Liar. You were in there for over half an hour. Debriefings for idiot cases never take more than ten, fifteen minutes. You made small talk. You got personal.”

Koontz spat out the word as if it were a communicable disease. Mike didn’t comment. He’d learned long ago that responding to Rusty’s tirades just added fuel to the fire. It was easier to let him burn out on his own.

“Mike! I was there the first time, remember? I watched the whole thing unfold like a damn train wreck. I know what I’m talking about.”

“Look,” Mike said, “Three monikers that start with V. Write them down.”

Koontz growled at him. Mike ignored the look and grabbed a pen. He didn’t want to talk about Sandra right now. He wanted to work, he wanted to escape from all the confusion a simple thirty-minute meeting could bring. Besides, he had a rule: He never discussed Sandra with Rusty, and he never discussed Rusty with Sandra. Their mutual dislike was their problem, not his.

“One V-dubb,” Mike read off to his partner, “one Vavoom, and one V-Vex. Vavoom is really Cheryl, so we’ll count her out.”

Koontz finally looked at the names. “Vavoom, huh? Wanna bet what her occupation is?”

“She’s fourteen. Maybe not.”

“Hah. Fourteen is prime age out there. I double my bet that she is.”

Mike shrugged. Koontz was probably right.

A long time ago, Mike had figured out that the trick to understanding Rusty was that for him, the world was actually a simple place. There were good people—cops—and bad people—everyone else. Which meant that, despite Sandra’s claims, Rusty was an equal-opportunity cynic. There wasn’t a person he met whom he didn’t assume the worst about, and not a man, woman or child whom he didn’t suspect. If he ever met Sandy’s well-groomed dad, Koontz would assume money laundering. If he ever met Sandy’s pristine mother, Koontz would assume plastic surgery and Valium. That was just his way.

“Try known associates,” Koontz said.

“I’m gettin’ there.” Mike typed in the search field and the ancient database whirled. The computer made an unhealthy sound, then coughed up an answer.

“Criminy,” Koontz said. “We gotta get some new hardware around here.”

“We did. White Collar grabbed them. Said they needed them more. All good fraud these days is on computer.”

“Ha, more likely all good computer games. What kind of caseload does WC have these days anyway? I say we wait until dark, then steal the computers back.”

Mike glanced over at his partner. It was always hard to tell when Koontz was joking.

“Zero matches found,” he said. “Your turn. On to NCIC.”

Koontz grudgingly traded places with Mike. Rusty was the most familiar with NCIC and already had the national crime database whirling as Mike rolled the first kink out of his neck.

“It’s odd that Vee doesn’t even appear as a known moniker,” Koontz grumbled.

“Unless he doesn’t actually belong to a gang.”

“The kid is thirteen. You don’t get to be thirteen on the east side without someone jumping you in.”

“A holdout? Maybe

outta respect for his brother.”

“Do we got a name for the brother?”

“Nope.”

“Damn. Dead end here, too.” Koontz pushed back from the computer, frowning harder. “He’s gotta be in the system.”

Mike agreed. “Known family associations with gangs. Street name, claims of being a straight shooter. You’d think we’d find a record.”

“Maybe it’s fake. Whole letter’s just a hoax to yank our chains. Someone out there likes toying with the men in blue.”

“Or maybe Vee’s a new moniker. Vee for vengeance.”

“Huh. It’s possible. Don’t know why these kids have to make up new names, though. It’s not like anyone in the east side is naming their son Bob anymore.”

“What about the Crime Scene Unit? They get any prints off the letter?”

“Wrecked,” Koontz told him. “Seems everybody at the newspaper touched it, so prints are impossible. Letter was hand-delivered, so no postage. Envelope not sealed so no saliva. Get this, the letter was actually typed. Old manual typewriter with Wite-Out for corrections. Not a neat job, but still means no handwriting analysis. Of course, we could probably match the letter to a particular typewriter, but that assumes we know enough to find the typewriter. Case is getting easier all the time, isn’t it?”

Mike sighed and picked up his jacket. “Only one thing left to do.”

“No…”

“We gotta find the kid somehow. Newspaper office sits on a major bus line.”

Koontz groaned louder. “Ah, nuts, I hate this kind of grunt work.”

“It’s not just a job,” Mike assured him. “It’s an adventure.”

Chapter 3

Driving to the bus station, Mike started thinking about his ex-wife again.

He didn’t want to. After the divorce, he’d adopted a strict policy of not looking back. He’d been raised with a certain philosophy about the world. Roll with the punches, live life easy. So he’d gotten a divorce. That’s the hand life had dealt him. Move on.

Besides, if he thought about it too much—remembered Sandra’s smile, her scent, the way she’d sigh right after he kissed her—he got angry. Angry that she was gone. Angry she hadn’t given them more of a chance. Angry that he was divorced, dammit, and he’d never wanted to be divorced. Would someone please tell him what the hell he was supposed to have done differently?

Mike didn’t like getting angry. So he made the rule about not looking back. Easygoing Rawlins. Rolling with the punches. Living life fine. Yeah, that was him.

Until today. Today was doing him in.

Sandra striding into the morning meeting, looking even better than he remembered. God, he loved it when she had her chin up and her eyes sparkling for a fight. Koontz had it all wrong. Mike had never minded that his wife could be bossy or tough. Hell, he’d loved that about her. Sandra was the first woman he’d ever met who couldn’t be swayed just by his grin. She gave as good as she got. She made him work for things. She made him feel alive. That was his wife.

And he knew the rest of her, too, the softer side she’d never show someone like Koontz. The late nights when she’d compulsively rub the back of her neck where her muscles knotted from carrying the weight of the world around with her all day. The next morning when she’d drag herself out of bed with the worst migraine rather than let her father’s company down. Then along the way to work, she’d stop and watch the little kids run through the park, because Sandy really wanted to have children and worried that she was too driven and career oriented to be a good mother.

Rainy days dragged her down. Sunny days perked her up. Her favorite treat was undercooked brownies eaten hot and gooey straight from the pan. And her favorite way of spending Sundays used to be in his arms.

Mike didn’t want to know how she was spending her Sundays now. That would make him angry. So he thought about their wedding, instead.

It had been in Boston, some huge stone church where all Aikenses had tied the knot since time immemorial. Sandy’s mom had hired a fancy florist to deck the place out in satin bows and white roses, and they’d triggered a pollen attack so bad Mike’s brother had to be led out of the church. Mike hadn’t really noticed.

His mother was still injured about the reception menu, he remembered that vaguely. She’d wanted to bring her special potato salad and Mrs. Aikens hadn’t taken that well. The event was being catered. Caterers didn’t need help. What were they thinking? Then his mom had offered Sandy her wedding headpiece, passed down for three generations, and that had also been refused. Instead Sandra had had some designer dress and veil custom-made for her on Newbury Street.

Mike hadn’t paid much attention to those things, either, though maybe he should have. At the time, none of it had mattered to him. Not Rusty’s dire predictions, nor his mother’s stiff stance, or his future in-laws’ condescending stares. So their parents didn’t get along, so they came from different worlds. Sandy drove herself hard. He lived life easy. She believed in fine dining, he loved a good barbecue. She played bridge with her family, he played coed tackle football with his.

Diversity was the spice of life. Love would get you through. If there was a platitude, he must have believed it back then. Because mostly, he’d believed so badly that he’d wanted Sandy.

And then, there she was. Standing at the head of the aisle. Framed by white roses with golden light from the stained-glass window pouring in behind her. He’d stopped breathing. His chest had gone so tight it hurt. Mon Dieu, she was lovely. Mon Dieu, she was his wife.

The rest of the world had ended for him then. If he hadn’t already fallen in love with her that first day, he fell twice as hard for her at that moment. He loved the strong, proud line of her shoulders. He loved the way she walked down the aisle, looking him right in the eye and never missing a step. He loved the way she clung to him after their first man-and-wife kiss and he loved the way a single tear had trickled down her cheek. “I love you, Mike Rawlins. And I’m so happy to be your wife.”

Later, much later, finally alone in their honeymoon suite, they’d both been curiously shy. Sandy had a confession to make. She’d been reading magazines on the subject. Lots of brides and grooms end up too exhausted by the end of the big day to have a traditional “wedding night.” So, if he was tired…they didn’t have to…she meant, if he didn’t want to…

Hell, there was nothing Mike had ever wanted more.

But it was funny, he’d taken it slow. He’d made love to a dozen women in his life. He’d made love to this woman over a dozen times. Sweet Lord, for the first month they hadn’t been able to keep their hands off each other. Still, this was their wedding night. She was his wife. It did something to him, made him feel the moment way down deep. He’d never spent so much time carefully slipping little pearl buttons free as he did that night. He’d never lingered for so long over each piece of clothing, peeling away satin and silk and froths of lace to reveal smooth, creamy skin and firm, ripe curves.

He hadn’t made love to Sandra that night; he’d devoured her. Slowly, carefully, exquisitely. Until he felt her soft, urgent sighs burn across his skin. Until her perfectly manicured nails dug into his back. Until the sweat was a fresh sheen across their bodies and she was wild beneath him.

And even then, some part of him didn’t want it to end. Some part of him would have dragged it out forever if only he’d known how. Maybe even back then, some part of him had known it could never last. She hadn’t even taken his name. How long before she decided she didn’t need the rest of him, either?

Still he had tried. Still he remembered those first days of marriage, when fierce, haughty Sandra Aikens had loved him and said she was proud to be his wife.

“What are you thinking about?” Koontz asked from the driver’s seat.

“Nothing.”

“Nothing,” Koontz observed, “doesn’t wear hundred-dollar perfume.”

They struck out at the bus station. The city bus passed the newspaper office every half hour, makin

g it hard to narrow down the time the letter was delivered, let alone by whom.

The station manager fetched the bus driver of the route for them, but when Koontz asked him if he’d carried a thirteen-year-old black kid lately, the man burst out laughing. He ran the east-west metro. About all he had on his buses were teenage black kids.

Next they tried the newspaper office. Surely they had people in all night, finishing stories, running presses. Newspapers never sleep, right?

Well, maybe in big cities. Alexandria’s Citizen’s Post, on the other hand, went to bed at eight each night. The presses ran all night long but, thanks to automation, took only six people to run. When the delivery crews arrived at five in the morning, they pulled up to the back, so no one noticed a letter in the front mail drop until offices opened at eight o’clock.

“Come on, don’t you guys at least have a janitor?” Koontz wanted to know.

“You mean Hank?”

“Sure, Hank. Let’s all go talk to Hank.”

They all went and talked to Hank. He was seventy-five years old and deaf as a doornail. Mike wasn’t sure, but he believed they finally established that Hank hadn’t seen anything. The security guard was worse. Mike and Rusty knew him from his former days as a cop. He’d been a drunkard then and apparently hadn’t done a thing to clean up his act. The editor-in-chief was sorry, but what more could he say? If they did learn anything, they’d pass it along, right? After all, Citizen’s Post had cooperated with them….

Koontz said, “Sure,” without blinking an eye, but Mike knew his partner was lying. Koontz held reporters in even greater contempt than defense attorneys.

Three-thirty in the afternoon, they descended the steps of the newspaper building.

“These kids are like ghosts,” Koontz muttered. “Who really pays attention to a lone thirteen-year-old anyway? Maybe we are safer when they’re traveling in packs.”

“Vee’s gotta be a new alias.”

“I don’t like it.” Koontz shook his head. He had a good instinct about these things, so if he was troubled, Mike was troubled.

Marrying Mike...Again

Marrying Mike...Again At the Midnight Hour

At the Midnight Hour The One Worth Waiting For

The One Worth Waiting For Hiding Jessica

Hiding Jessica Brandon's Bride

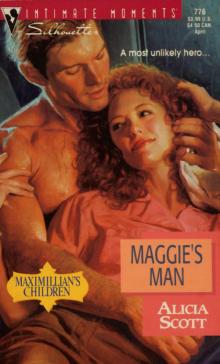

Brandon's Bride Maggie's Man: A Family Secrets

Maggie's Man: A Family Secrets Macnamara's Woman

Macnamara's Woman Partners in Crime

Partners in Crime Maggie's Man

Maggie's Man